Agriculture Science

35

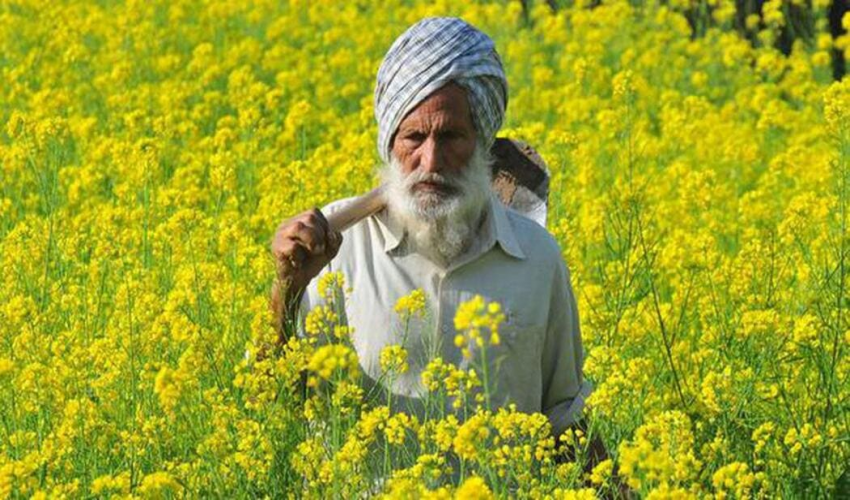

The modern hybrid form of mustard

- Rating

- transgenic

- haryana

- genetically

- crops

- produce

- hybrid

Up to this point: The genetically altered mustard variety Dhara Mustard Hybrid-11 (DMH-11) has been given the green light for environmental release by India's highest authority on GM crops and foods, the Genetic Engineering Appraisal Committee (GEAC). If it gets the green light for commercial production, it would be the first GM crop accessible to Indian farmers.

DMH-11, what is it?

The Centre for Genetic Manipulation of Crop Plants at the University of Delhi created the hybrid mustard variety DMH-11. Former University Vice Chancellor and longtime leader in the development of hybrid mustard at the Centre, Deepak Pental, started with DMH-1, a hybrid variety produced without transgenic technology. Despite the fact that experts have indicated DMH-1 isn't a reliable enough technology to reliably generate hybrid mustard, it was released commercially in northwest India between 2005 and 2006. Although there are many mustard varieties in India, it is difficult for plant breeders to cross them and induce desired features since mustard is a self-pollinating plant. The self-pollinating feature of the mustard plant is to be turned off to allow for such crosses and then turned back on to allow for seed production. DMH-11 originated from a hybridization of two different cultivars, Varuna and Early Heera-2. The genes from two soil bacteria, barnase and barstar, were introduced to generate a cross that would never have occurred spontaneously. Barnase causes temporary sterility in Varuna, making self-pollination impossible in the wild. Heera's barstar prevents barnase from doing its damage, which allows the plant to generate seeds. Better yield and fertility are the results of DMH-11 (where 11 is the number of generations after which beneficial features appear). Because it incorporates genes from a different species, DMH-11 is considered a transgenic crop.

Have improved hybrid mustards been developed?

According to three years' worth of trials done by the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), DMH-11 produces 28% more than its parent Varuna and 37% more than zonal checks, or local varieties that are deemed the best in distinct agro-climatic zones. Over the course of three years, eight different locales participated in these tests. Instead of being an end in itself, DMH-11 is a platform technology that demonstrates the efficacy of the barnase-barstar system and may be used to create other hybrids. Better hybrids are needed, according to scientists, to reduce India's growing reliance on imported edible oil. During the Rabi winter season, the states of Rajasthan, Haryana, Punjab, and Madhya Pradesh devote the majority of their farmland to growing mustard (Brassica juncea). About 55-60% of India's annual need for edible oil is met by imports. According to the National Academy of Agricultural Sciences, in 2020–21, the country imported over 13.3 million tonnes of edible oil at a total cost of about 1,17,000 crore. For nearly two decades, production has been low, at about 1.1–1.3 metric tonnes per hectare. In contrast, oil seeds grown in Canada, China, and Europe are mostly hybrids of mustard and rapeseed. The only way to increase India's output, they argue, is to grow more mustard hybrids.

What about it causes debate?

There are primarily two points of contention with transgenic mustards. Mustard hybrids can only be prepared with the use of a gene called the bar gene, which confers tolerance to the herbicide glufosinate-ammonium. This is one example of the usage of non-native genes. Protesters say the safety of the herbicide-tolerant GM mustard hasn't been assessed. Finally, they claim that GM mustard plants might cause environmental disaster by discouraging bees from pollinating the plant. The Rashtriya Swayam Sevak Sangh's allied organisation, the Swadeshi Jagran Manch, has always been a vocal opponent of genetically modified (GM) crops, and it has provided funding and assistance to activist organisations.

Is there a future for genetically modified mustard?

The GEAC has already approved the release of genetically modified mustard into the wild. Again in 2017, the highest authority gave its approval, but this time the process was halted when a lawsuit was filed in the Supreme Court. Although the GEAC reports to the Environment Ministry, the government has not given its approval of genetically modified mustard. The first transgenic food crop, Bt Brinjal, was approved by the GEAC in 2009, but the then-UPA administration put it on hold due to the need for additional testing. In the present, Bt-cotton is the only transgenic crop produced in India. The approval from the GEAC restricts the cultivation of DMH-11 to farms overseen by the ICAR. After "three seasons," according to the Indian Agricultural Research Institute, the crop will be commercially accessible because it can be produced in sufficient numbers for testing.

The Dhara Mustard Hybrid-11 (DMH-11) has been certified for environmental release by the Genetic Engineering Appraisal Committee (GEAC), India's top regulator of genetically modified plants and food items.

Mustard is a self-pollinating plant, making it difficult for plant breeders to cross types to create new ones with desired characteristics. India is home to several mustard varieties.

During three years of testing by the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), DMH-11 was found to produce 28% more than its parent Varuna and 37% more than zonal checks, or local varieties that are regarded the best in distinct agro-climatic zones.

During the Rabi winter season, Rajasthan, Haryana, Punjab, and Madhya Pradesh account for the vast majority of the 6-7 million hectares dedicated to growing mustard (Brassica juncea).

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *