Religious Studies

5

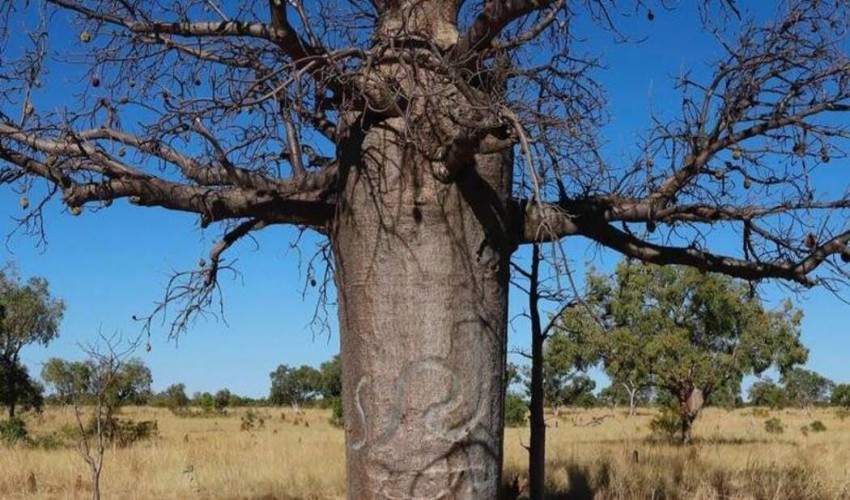

The boab trees of Australia have carvings that tell the narrative of a forgotten generation.

- Rating

- archaeologists

- ancestors

- grandparents

- engravings

- kimberley

Brenda Garstone is looking for her family history.

Dozens of old boab trees in the Tanami desert in northern Australia are etched with Aboriginal motifs, representing a piece of her cultural legacy. Dendroglyphs are engravings made into trees that may be thousands of years old yet have gotten absolutely little attention from western scholars.

And yet, things are beginning to shift. Garstone, an Aboriginal man from the Kimberley area of northern Australia, collaborated with archaeologists in the winter of 2021 to locate and record some of these engravings.

This journey represented Garstone's attempt to reassemble the fragments of her identity. 70 years ago, when Garstone's mother and three siblings were among the estimated 100,000 Aboriginal children removed from their homes by the Australian government, these pieces were dispersed. The twins, like many others, were exiled to a Christian mission hundreds of kilometres away from home. For Garstone's family to recover its heritage, it would require decades of work and a chain of seemingly unrelated occurrences, such as the donation of an heirloom and the pursuit of information about a vanished 19th-century European naturalist.

In the country of their mother's birth, the Garstone children's extended family presented Anne Rivers, Garstone's aunt, with a coolamon, a shallow dish adorned with two bottle trees (or boabs). When Rivers, then only two months old, was taken away, she was informed that the trees were significant in her mother's Dreaming, the traditional myth that bound her and her family to the land.

Scientists have now detailed in detail 12 boabs with dendroglyphs in the Tanami desert that have ties to Jaru civilisation. The report was published on October 11 in Antiquity. And just in time: the trees that hold these ancient carvings are dying from the effects of time and increasing pressure from cattle and probably climate change.

It's not merely an issue of preserving history by recording these engravings before they go. It's also about mending the fences that were put up by policies that sought to sever the ties between Garstone's ancestors and the land.

Finding "evidence that binds us to the land" has been "wonderful," she adds. "We've finally put the last piece in place of the puzzle we've been working on."

The boabs (Adansonia gregorii) from Australia's outback proven to be an essential resource. Boabs are a distinctive kind of tree native to the northwest of Australia, distinguished by their huge trunks and distinctive bottle form.

Since the early 1900s, anthropologists have documented the presence of trees in Australia that have been intricately carved with Aboriginal motifs. According to these documents, individuals continued to carve and recarve at least some trees into the 1960s. Moya Smith, curator of anthropology and archaeology at the Western Australia Museum in Perth, who was not involved in the study, says that "there does not appear to be a wide general awareness of this art form," especially when compared to the visually spectacular paintings also found in the area (SN: 2/5/20).

When it comes to carved boabs, Darrell Lewis has seen his fair share. The historian and archaeologist who has spent the last fifty years working in the Northern Territory is currently based at the University of New England in Adelaide. Lewis has uncovered petroglyphs carved by cattle drovers, World War II troops, and Aboriginal people. A tangible monument to the individuals who have made this harsh area of Australia their home, he refers to this assortment of engravings as "the outback archive."

In 2008, Lewis went looking for what he anticipated would be his most significant archival find in the Tanami Desert. He'd overheard tales of a cattle drover who'd worked in the region a century ago discovering a gun hidden in a "L"-marked boab. The famous German scientist Ludwig Leichhardt vanished in 1848 while trekking through western Australia, and his name is stamped on a poorly cast brass plate from the pistol that was eventually purchased by the National Museum of Australia.

The boab is not often seen in the Tanami. To find the Tanami's hidden hoard of boabs, Lewis leased a helicopter and flew back and forth over the desert in 2007. His aerial surveys of the desert uncovered hundreds of younger trees and around 280 boabs that are millennia old.

Off the beaten path and into the Tanami

The party left the town of Halls Creek on a winter day in 2021 and camped out on a distant pastoral property inhabited largely by livestock and stray camels. Using all-wheel-drive vehicles, the crew set out daily to the last known site of the etched boabs.

To put it simply, it was strenuous. The team would drive for hours to what they thought was the location of a boab, only to have to stand on the roofs of their trucks and look for trees in the distance. Tires were continually being torn by protruding wooden spikes. O'Connor claims that they were "out there" for a total of eight to ten days. As one person put it, "It seemed longer."

After seeing 12 trees covered with dendroglyphs, the excursion was cut short because they had run out of tyres. When documenting their discoveries, archaeologists took hundreds of photos that overlapped, allowing them to record every inch of every tree.

The group also found artefacts like grinding stones and other implements strewn among the tree roots. The researchers conclude that humans likely utilised the trees as resting locations and navigational markers when trekking through the desert since the enormous boabs give shade in a desert with little shelter.

On several of the boabs were depictions of emu and kangaroo paw prints. A large number of the carvings, however, depicted snakes, some of which writhed over the bark and others which curled in on themselves. Historical documents from the region, as well as the information supplied by Garstone and her family, all point to the King Brown Snake Dreaming as the possible inspiration for the sculptures.

"It was strange," Garstone says. She claims the dendroglyphs are "pure proof" of the ancient link to country, validating the legends handed down via her family. Particularly for her mother and aunt, both of whom are now in their 70s, the rediscovery has been a cathartic experience. They didn't have the opportunity to learn these things from their parents and grandparents, so "almost everything was gone," she adds.

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *